Story and Data: Three Make or Break Moments in Story History

- Written by Alex Chantilas

“Maybe stories are just data with a soul.”

Brené Brown

Everyone learns differently. Some people need hard facts, data, and statistics before they can be persuaded of anything. We wish those people well, and hope they use their understanding of data for good, but to most people, a story that speaks to a human narrative is significantly more compelling than a standalone statistic, academic paper, or dataset.

The stories we believe make up our reality, and that’s why it’s so important for professional storytellers to rely on data to support their claims. Below, we’ve compiled some of the most striking examples that demonstrate the complicated and coalescing relationship between story and data.

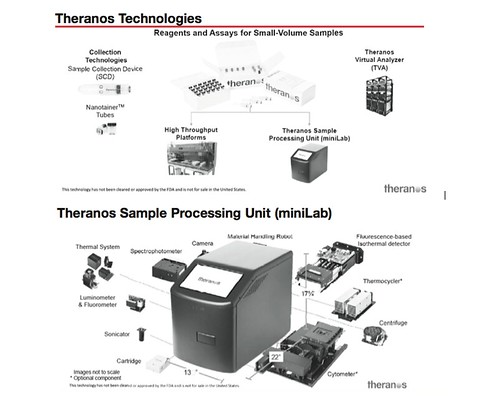

Theranos – where story failed without data

The Story

Elizabeth Holmes, Stanford dropout and Theranos founder, constructed a narrative capitalising on the public’s fear of needles–pitching a revolutionary blood test that claimed to use just a single drop of blood to test a multitude of diseases.

Holmes’s storytelling abilities precede her. She amassed a cult of personality which persists today as we greedily consume coverage of her criminal trial, and “holmies” merchandise her face on phone cases, clothing, and furnishings alike. Holmes dropped out of university in the name of a noble idea, an origin following the footsteps of Silicon Valley gods like Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg.

Understanding the potency of a persuasive story, she hired an academy-award winning documentarian to create ads for Theranos’ innovation. In the process of building the brand, Holmes collected cover features on Fortune Magazine, New York Times Style, and Glamour before the product really even did anything. Her story enraptured millions and her company’s valuation reached $10 billion in just over a decade. Complete outsiders to the biotechnology field like Walgreens, Henry Kissinger, Rupert Murdoch, and George Schultz were in awe of Theranos – they invested millions.

The Data

Behind veiled terms like “trade secrets,” Theranos’s facade went unchecked for years. Ultimately, Theranos’s story crumbled when it couldn’t change science enough to fit the narrative it built. The Stanford medical school professor to whom Holmes pitched her original idea knew the technology she aspired to develop could never work. But when Theranos attempted to develop it, the Edison Machines couldn’t regulate their temperature or deliver test results with the drop of blood that Theranos had built its mythos around.

Ultimately, Whistleblowers, scientists, and reporters worked together to debunk the company’s fraudulent and exploitative practices/technology. Once the youngest self-made billionaire of all time, Holmes now faces up to 20 years in prison for criminal fraud. Despite her extraordinary ability to gather momentum around a compelling story, Holmes couldn’t overcome the lack of data behind her firm’s claims that its products could revolutionize the $75 billion blood test industry.

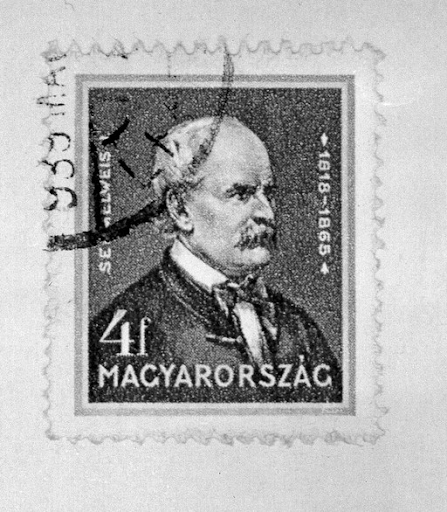

Ignaz Semmelweis – where data failed without story:

It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.

Voltaire

The Data

In 1846, Ignaz Semmelweiss was appointed as an assistant at a Vienna teaching hospital with two maternity clinics run by doctors and midwives in training. The clinic often took in poor women and sex workers who had become pregnant. The doctors’ ward was notorious for the deaths of mothers and a high infant mortality rate, while the midwives performed consistently better on ensuring safe births. Semmelweiss took note of the discrepancy in mortality rates between wards, and tested variable practices in birthing with the scientific method–no luck. After a physician received a cut from a blade used in an autopsy on one of the pregnant women, and died with the same symptoms she had, Semmelweiss knew he was onto something. Revelation came when he implemented a handwashing regime for his colleagues between the morning autopsies and afternoon births they facilitated.

After hand washing was instituted, the mortality rate in the doctor’s ward declined 90%. A year following this discovery, the mortality rate dropped down to zero for at least two months.

The handwashing regime implemented with a chlorine rinse improved the quality of care given to mothers, chemist Louis Pasteur wouldn’t have discovered germ theory until over 20 years later. What the doctor had was more than 18 months of statistical data showing his hand washing approach worked and that such practices could save the lives of thousands of expectant mothers. He had the truth—but it wasn’t enough.

The Story

Rather than lauding Semmelweis’s valuable discovery and adopting his methods throughout the world, he faced sharp criticism, ridicule and resistance from the established medical community. Semmelweiss’s step towards germ theory was in sharp opposition to the narrative that sickness came from “bad air,” and when he left the hospital, his colleagues resumed their original practice. American obstetrician of the time, Charles Meigs’s rebuke was clear: “Doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman’s hands are clean.”

The Vienna teaching hospital was the primary cause of the deaths of lower class women’s lives. Lives that could have been saved improved hygiene from the physicians caring for them. Eventually, Semmelweiss died a pariah in the eyes of the medical community. He ultimately died of the yet-named pathogen he obsessed over his whole life: sepsis.

Ni Una Menos – Story and Data in Harmony:

The Story

In 2015, the brutal murder of a 14-year-old Argentinian sparked a movement. Chiara Páez, was beaten to death by her 16 year old boyfriend, she was pregnant at the time. Her death, along with other high-profile murders of young women across Argentina, was a breaking point for women. In Argentina one woman is killed every 32 hours.

Following the murders, tens of thousands of women took to the Argentinian streets in protest. Holding signs reading Ni Una Menos, or Not One Less, women young and old came together to demand systemic change.

The Data

The practice of data activism became a critical form of feminist resistance–activists and partners created a nationwide citizen index of reliable data, the Observatory of Femicide, providing people powered data to media outlets for reports on gendered violence.The project generated national statistics to expose the sheer scale and nature of gendered violence, and Within the three month period, over 60,000 responses were collected from women all over the country.

The results were sobering; over 97% of the women who completed the survey suffered some kind of gender violence, but only 5% had reported it to the police. Over 20% said they were violated.

#NiUnaMenos presented the results on International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and the survey exposed these violations, applied pressure to civil society and authorities, and demanded change.

So now you’ve seen what stories backed (or not) by data can do. They can create (or destroy) fortunes. They can build (or kill) reputations. And they can expose truths that save millions of lives. So go forth–build your story. But please, do your research.

Share:

Grow Your Good Idea Faster

New ideas are precious. Win support by learning how to create and tell a stronger story – sign up to join for free.

Related posts

Business as Unusual: Anita Roddick and The Body Shop

Anita Roddick, activist and founder of The Body Shop, was someone who married her products with politics. Her life and...

When nature lovers are bad for our planet

There are many different ways to feel a connection with nature, but strict tribal definitions stop most of us from...

Fight, flight, freeze, fawn: Injecting courage into your story

Fight, flight, freeze and fawn – we all have these instincts. These physiological reactions in our nervous system...

Learn from the strongest stories about change

Sign up here to receive our monthly newsletter that explores great storytelling about brilliant ideas. Don’t worry you can unsubscribe at any time.

We’re working hard to walk the talk.

We’re proud to be have been awarded The Blueprint and B Corp status in recognition of our work towards creating a better world.